Gender pay reporting aims to help employers identify and close pay gaps in their organisations, but is it having any real impact?

by Sally Percy

According to the World Economic Forum’s Global gender gap report 2021, which covers 156 countries, the global wage gap (the ratio of the wage of women to that of men in a similar position) is approximately 37%. Wage gaps exist in even the best performing countries on the WEF’s index, including Iceland (14%), Rwanda (19.1%) and Finland (20.3%). There is no country in the world where the wage gap has entirely closed.

The WEF report uses four subindexes to measure gender gaps, with wages forming part of the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex, which also looks at representation in the labour market, senior and managerial positions, wages, unpaid work, and financial inclusion. The average across the four subindexes shows a global "average distance to parity at 68%, a step back from 2020 (-0.6 percentage points)", with a current trajectory of "135.6 years to close the gender gap worldwide", it says.

The subindexes and percentage of the gender gap closed in 2021 are, according to the report:

- Educational Attainment subindex: 95%

- Health and Survival subindex: 96%

- Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex: 58%

- Political Empowerment subindex: 22%

The UK has one of the highest gender pay gaps in Europe, according to 2019 analysis by Statista. Analysis by the Financial Times finds that in April 2020, women were paid 87p for every £1 paid to men. What’s more, the financial and insurance sector notably has the biggest gender pay gap of all sectors in the UK – at 30% – according to 2021 data by Statista, with this disparity often attributed to a lack of women in senior jobs. The picture is similar in the US, where data from the US Census Bureau reveals that women in financial services earn just 60.3% of what men earn.

In October 2021, Reuters analysed the pay gap data from 21 major financial insititutions, finding that “major banks had only made a slight dent in their gender pay gaps” since the previous year, while “several insurers went backwards”. Reuters identifies insurer Admiral as the only large firm surveyed that “had a gender pay gap [12.8% for the 2020/21] lower than the most recently published average across all sectors”.

Admiral’s gender pay gap report 2020 explains how it has achieved this, through initiatives including gender neutral wording in job advertisements, gender balanced shortlists, and “building a research and networking community for parents and carers”.

Gender pay gap reporting

Over the past couple of years, the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated gender inequality around the world. Women were more likely to lose their jobs during the crisis and were more likely to take on extra home-schooling responsibilities. In the UK, mandatory gender pay gap reporting was even temporarily suspended during the pandemic.

Gender pay gap reporting was introduced in the UK in April 2017. Other countries that use gender pay gap reporting include Australia, France, South Africa, Spain and Sweden.

The gender pay gap is the difference in the average hourly wage between men and women in an organisation; it is not the same as unequal pay Under the UK legislation, employers with 250 or more employees are required to publish their gender pay gap. The gender pay gap is defined by the government as the difference in the average hourly wage between women and men in an organisation, expressed as a percentage of average male earnings. “It is not the same as unequal pay, which is paying men and women differently for performing the same (or similar) work. Unequal pay has been unlawful since 1970”, it says.

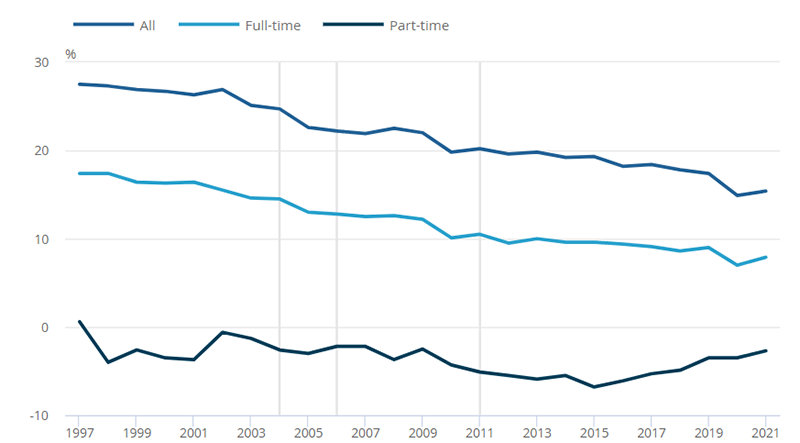

Gender pay reporting aims to help employers identify and close gender pay gaps in their organisations, and statistics suggest that it might have made a difference since it was introduced in 2017. In 2021, the UK’s median gender pay gap was 15.4%, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), down from 18.4% in 2017. But the gap has been declining slowly over time anyway, falling from 27.5% in 1997. Nevertheless, the fact remains that, looking at the average across all jobs, the gender pay gap persists.

Gender pay gap for median gross hourly earnings (excluding overtime), UK, April 1997 to 2021

Source: Office for National Statistics – Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings

Source: Office for National Statistics – Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings

Rita Trehan, CEO of transformation consultancy DARE Worldwide, believes that the sluggish progress to date is partly down to employers abiding by the letter of the law, but not necessarily heeding the spirit of it. “When the government first put in place the need to report on gender pay rates, you saw employers step up to understand the importance of it,” she says.

“But what we’ve seen in the past year is that it’s become ‘just one of those things we’ve got to do’. So, I would say, are we making progress? Yes. Could we say it’s significant? No. Is there an opportunity for companies to be doing more? Absolutely.”

Large UK employers are obliged to publish their gender pay gap information, but the publication of a supporting narrative and action plan is discretionary. Effectively this allows them to avoid tackling their gender pay disparities. “The issue is that the reporting, in itself, is reporting,” says Rita. "It’s not actionable insights on what employers are going to do. Employers should be asking the ‘why’ questions. Why is it that we’ve still got this problem? Why are we not getting enough women surfacing through our talent processes?”

Action plans are vital to addressing the issues associated with gender pay inequity. “In my experience, organisations that have managed to close their gender pay gaps have set very clear action plans, which have not only been communicated broadly to their internal and external stakeholders, but have also been followed through,” notes Paul Modley, director of diversity, equity and inclusion at workforce solutions firm AMS.

“These plans have been very much focused on creating an environment for all to succeed in their business, removing barriers to progression and establishing an employee value proposition that is attractive to all.”

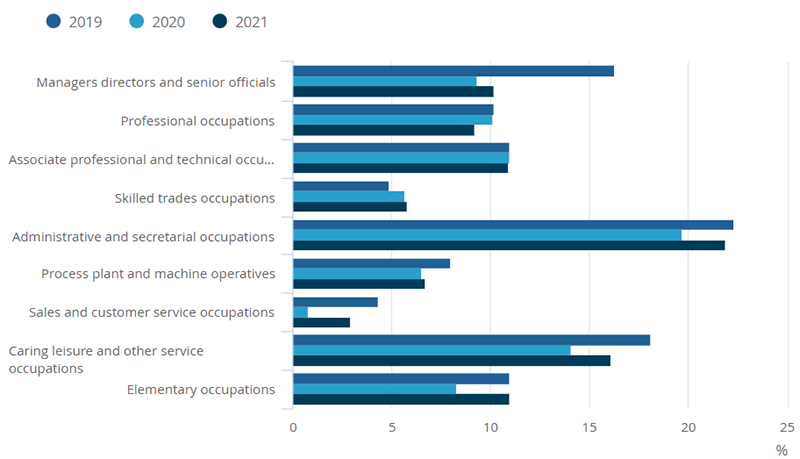

Closing the gap

One explanation for the gender pay gap is that women are more likely than men to work part-time, with part-time hourly pay being lower than for full-time workers, according to a report published in May 2020 by the UK Parliament. It could also be a result of fewer women in senior roles – the report shares 2019 data that shows 28% of women versus 13% of men in low-paying occupations and, on the other end of the scale, 18% of women versus 26% of men in high-paying occupations. But there is a marked improvement in 2021, with ONS data showing that “the largest fall in the gender pay gap since before the pandemic is among managers, directors and senior officials”, from a gap of 16.3% in 2019 to 10.2% in 2021, “reflecting some signs of more women holding higher-paid managerial roles”.

Gender pay gap for full-time median gross hourly earnings (excluding overtime), by occupation, UK, April 2019 to 2021

Source: Office for National Statistics – Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings

Taking a broader view across all sectors, the widespread shift to remote working that has accompanied the pandemic could have a negative impact on women’s pay going forward.

This is the view of Teresa Boughey, CEO of Jungle HR and member of the Women and Work All Parliamentary Group. “We heard, coming out of the pandemic, that lots of organisations were considering adjusting their reward strategy for individuals working remotely,” she says. “They were even suggesting pay cuts. But who is likely to want this kind of working and are we penalising those individuals? If organisations haven’t already done it, I think this is an opportune moment for them to reflect on their reward strategies.”

Teresa believes that for employers to gain real transparency around their performance on gender pay, they need to make use of people data dashboards that provide real-time insights around diversity and inclusion. “Make sure you’re taking a regular temperature check in terms of what’s happening with your people,” she says.

Technological tools can help employers to understand where and why pay gaps exist within their organisation so they can improve pay equity going forward. “Technology exists today to quickly analyse all compensation, identify people who are underpaid because of gender, and resolve the underlying behaviours driving the issue to begin with,” explains Zev Egein, founder of workplace equity platform Syndio.

Women at the top

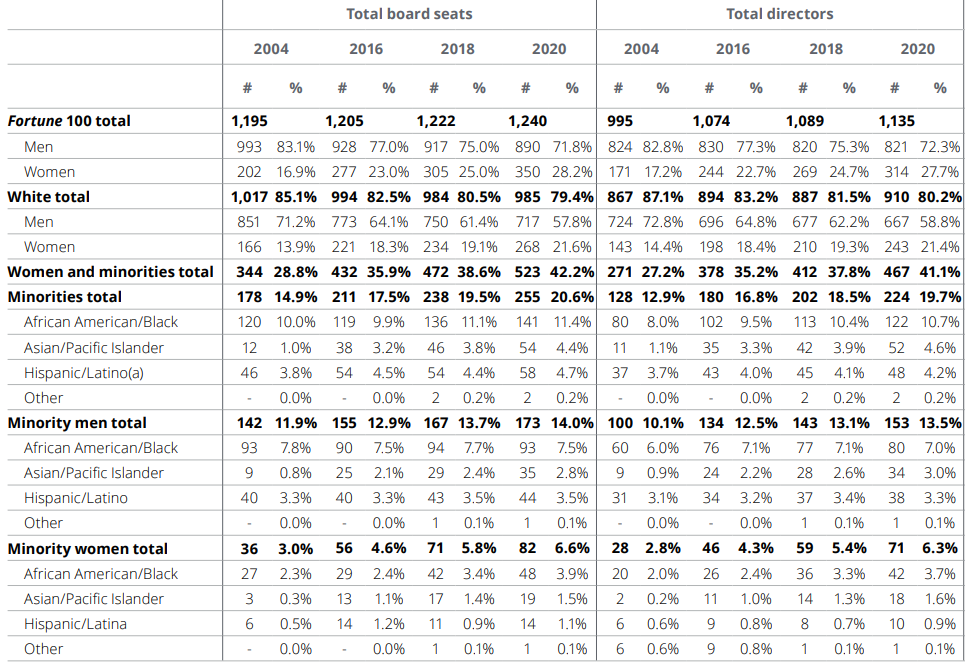

Since the underrepresentation of women in senior roles contributes to the gender pay gap, narrowing this gap depends on more women reaching the boardroom. Unfortunately, however, only 19.7% of board seats globally are held by women, an increase of just 2.8 percentage points since 2018, according to research published in February 2022 – covering nearly 10,500 companies in 51 countries – by professional services firm Deloitte, titled Women in the boardroom: A global perspective.

“In many cases, the gender pay gap exists because men occupy the majority of the most senior – and therefore highest-paid – positions of an organisation,” explains Sharon Thorne, Deloitte’s global board chair. “To address this, we need to take action to increase the number of women in the most senior roles – especially commercial and operational roles up to and including CEO.”

Sharon suggests that organisations invest in development opportunities for women throughout their careers, but particularly at the critical middle manager level. She also believes that advancing gender equality “has to be a priority for each CEO and board, with tangible benchmarks that can be tracked and measured”. She adds: “The CEO must lead from the front and make it a business imperative – setting targets, holding their leadership teams accountable, and tying recognition and reward to those targets and wider environmental, social and governance targets.”

The ethnicity pay gap

Delving deeper into the gender pay gap, further disparities are evident amongst different ethnicities. In 2021, a study by the London School of Economics finds that black women are the least likely to be among the UK’s top earners compared with any other racial or gender group. While 1.3% of UK-born white men are in the top 1% of earners, only 0.2% of UK-born white women fall into this category and less than 0.1% of UK-born black women.

Over the past few years, the lack of ethnic diversity at the top of British organisations has attracted increased attention. This is partly in response to the Parker Review, an independent review by Sir John Parker that focuses on improving the ethnic and cultural diversity of UK boards. The first report in 2017 recommends that all FTSE 100 boards should have “at least one director of colour by 2021”. By November 2020, 74 FTSE 100 companies had ethnic minority representation on their boards, 46% of whom are women, according to a press release by EY, which was involved in producing the Parker Review.

But these statistics don’t tell the whole story. Significantly, a 2021 study of the UK’s 150 largest listed companies by executive search firm Spencer Stuart finds that minority ethnic women only make up 5% of board members. The picture isn’t much better in the US, where research by Deloitte in 2020 finds that minority ethnic women hold just 6.6% of board seats. In contrast, minority men hold 14% of board seats and white women held 21.6% of board seats.

Fortune 100 board diversity data

Source: Missing pieces report:The board diversity censusof women and minorities on Fortune 500 boards, 6th edition

The UK Chapter of diversity campaign group the 30% Club is pushing for greater progress when it comes to getting minority ethnic women onto boards. It wants to see one person of colour at both board level and executive committee level of the FTSE 350 by the end of 2023 and hopes that “at least half of those seats go to women of colour”.

Pavita Cooper, vice chair of the 30% Club, notes that women of colour have often taken “less traditional career paths to the top”. For example, they might have founded their own businesses, or come up through HR or marketing, rather than held more commercially-oriented roles. She also points out that while women and ethnic minorities are often heavily mentored – meaning they receive guidance and support from other professionals – they tend to be under-sponsored. A sponsor is a senior leader who advocates for them – for example, by endorsing their candidacy for non-executive director opportunities. Pavita adds: “They don't necessarily have someone in their network helping them, like a chair, who might recommend them to a head hunter or another chair.”

Ultimately, progression and pay go together for all women, who can, when they reach boardrooms, advocate for greater equality and pay equity within their organisations.

“It’s important that we have more women with a seat at the table,” says Nabila Salem, president of cloud tech talent creation specialist Revolent. “Otherwise, how will anything change? If you give people who recognise and understand discrimination a chair at the table where big decisions are made, of course they’re going to try and reduce that discrimination.”